More-than-human-centered Design: From Bauhaus to Neuhaus

Saving our planet requires a revolution within ourselves – a paradigm shift in thinking – from separateness to connectedness.

There is a framework through which we perceive and relate to the world. In the 20th century, the idea that language defines the human experience became the popular belief, and so did it develop the foundation of our relationship with nature. What we could not describe or experience as humans, we turned a blind eye to. The realms of non-human experience outside human language were silenced, rendered voiceless and consigned to linguistic Otherness. This narrow way of thinking, absence of space for the Other and lack of listening and negotiating, by default, came to govern the ecological social space and resulted in a catastrophic imbalance in ecological awareness. The crisis in today’s status of flora and fauna should force us to rethink how we interact with them.

This year, Het Nieuwe Instituut joins the celebration of Bauhaus’ centennial by transforming into Neuhaus, a temporary academy for more-than-human knowledge, from May to September 2019.

Founded in 1919, Bauhaus aimed to shape a new liberated society through radical design and education innovation after the First World War. Meanwhile, today’s ecological and socio-political crises form a sardonic reflection of that time. However, instead of merely glorifying its past successes, Neuhaus resurrects the spirit of Bauhaus, embodying it through a curriculum of knowledge and practices in response to the current planetary crisis.

In launching its curriculum, Neuhaus hosted a symposium in which philosophers, biologists, artists and designers discussed what it means to design for the more-than-human. In between discussions were a series of performances, and, in the evening, a more-than-human costume party.

Performance by Iris Woutera. Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn.

Costumes from the more-than-human party. Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn.

Border Objects

As part of the program, (un)known collective, a group of students from the Design Academy Eindhoven, conducted an open forum about a new design methodology, which they explored through the design of “border objects”, or rather, “constructed objects that facilitate, trigger or simply illustrate the collision, friction or interaction between human and more-than-human agents”, allowing for the formation of non-anthropocentric perspectives.

As it’s completely uncharted territory both for the fields of design and communication, the challenge in framing multi-species collaboration lies in electing the right platform through which to represent the more-than-human voice.

Earlier in the symposium, Italian philosopher Frederico Campagna talked about war strategy and how, if in any battle, one lets his enemy choose the terrain, he will almost always certainly lose. In the attempt to foster multi-species collaboration, what methodologies must we use to select the right mediums and platforms such that we do not in fact render the Other voiceless? How do we listen? How can we let them choose? For (un)known collective, the design of border objects is just the start of prefiguring a new world – an incitement of transformative thinking.

In an attempt to foster multi-species collaboration, what methodologies must we use to select the right mediums and platforms such that we do not, in fact, render the Other voiceless?

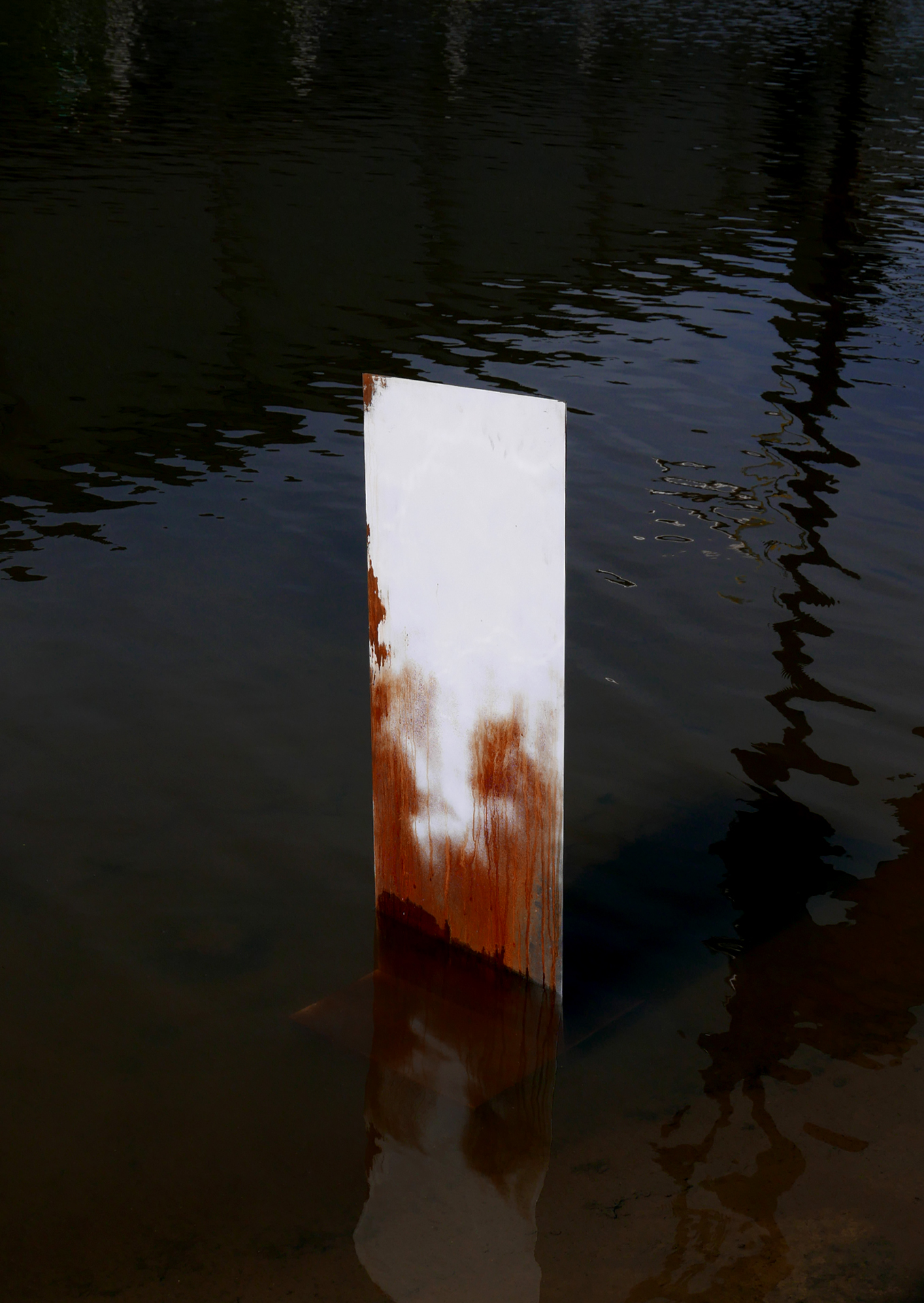

Border Object. Photo by Zan Kobal.

Border Object. Photo by Zan Kobal.

The Agora

It’s interesting to note that this multi-species discussion took place in a sub-venue of Het Nieuwe Instituut called “the Agora”, an open concave space with bleachers. Guests from diverse backgrounds sat around each other and in between border objects. A coalition of curators, scientists, teachers and artists engaged in critical discourse about what it means to design for the more-than-human. Each had a turn to speak with undivided attention; this was the appropriated democratic space.

Multi-species discussion facilitated by (un)known collective. Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn.

In Classical urbanism, two types of public spaces offered distinctly different opportunities to interact with Others. One was the pnyx, an amphitheatre used for debates and collective discussions; the other was the agora, the town square in which people were exposed to a diversity of people and activities in a more raw and direct manner.

The Pnyx was a bowl-shaped open-air theatre close the the Athenian central square. Resembling other Greek theatres, it was originally used for performances, but in the sixth and fifth centuries, it became a place for politics as well.

Speakers stood in the round open space, on a platform called a bema. From day to dusk, the sun shone on the speaker’s face, illuminating his expressions and gestures; nothing was left obscured by shadow. Words seemed to echo; the vast space between the speaker and his audience gave his voice a persuasive power. It allowed for words to marinade in the air and ideas to linger; positions were effectively expressed. Meanwhile, citizens sitting around the theatre observed each other as well, their reactions vividly captured as they watched the orator make his statements at the bema. This was the magic of the political theatre.

The other political space was called the agora. It was a town square, a large open space diagonally crossed by the Athenian main street. It was used for various activities such as commerce, religious rituals and informal socializing; multiple activities occurred at the same time, with minimal visual barriers so that each person could take part in different events at any given moment. There was a law court in the open space. It had low walls so that even those who were trading or making religious offerings could participate. In coming to the agora to offer up gifts to the gods, one could easily get caught up in commercial or political affairs as well. However, the agora also allowed one to withdraw his engagement. Under a roof on its open side, one could transition from the public to a private space.

Messy, coequal and unsorted, the visual elements of the agora largely shaped people’s experience of language. Words became fragmented as one moved from one space to another. Communication lacked the continuity which the pnyx, on the other hand, made possible. Movement of the eye was rapid and attention was divided in the agora, compared to the singularity of presence one would experience in a theatre.

Public spaces where diverse groups of people can come to interact fundamentally shape the politics of a society. However, exposure to diversity is not the only precondition for democracy. Different groups and persons that are merely concentrated in one place remain prone to isolation and segregation. For a space to be truly democratic, they need to truly engage.

What can we learn from ancient theatres and town squares that we can integrate into the design of our cities today?

This ancient example provides us alternatives for experiencing Otherness, be it in a raw unmediated form or a more structured deliberate manner. It allows us to think about how our cities should be built today so that each person, animal, plant and machine has a voice that not merely echoes into a void but is in fact heard and manifested into social reality. This is the foundation of democracy, and it is for this reason that designers need to seriously consider architecture as potential political spaces, not just as places to gather or expose each other to difference, but as places where concentration, deliberation and social transformation becomes possible.

Note: This article was originally published in the blog Architect Your Life on June 12, 2019.

References:

(un)known collective. Border Objects. 2019.

Sennett, Richard. “The Pnyx and The Agora” in Designing Politics: The Limits of Design. Theatrum Mundi - LSE Cities - Fondation Maison des sciences de l'homme. 2016